Is the oil sector changing?

If we persist with our irrational opposition to every type of scientific research, resting on our laurels, the price that we will pay will only get higher. Luckily, after years and years of pity party, hoping in public aids, the producers now are starting to change attitude. We are finally hearing about projects aimed at renovating and increasing production

We had been hoping for quite a while that Italy would increase its olive production. Now, after many years of crisis in our olive farming and oil-making sectors, things are starting to change. The producers are no longer doing nothing and feeling sorry for themselves, hoping and praying for public funds to help them face the expenses for the maintenance and indispensable updates of their production systems.

Now at last we are hearing about projects aimed at renovating and increasing production.

Money has mostly been invested in plantations. We have finally realized that the made-in-Italy claim alone cannot revive the economy of this sector, unless it is supported by adequate levels of quality and quantity. It is to be hoped that from now on we shall see fewer olive groves in a state of neglect.

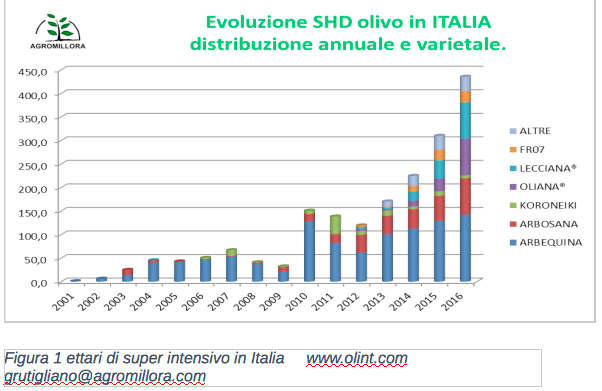

In the past two years, over 300 hectares of super-intensive olive plantations have been established in the environs of Bari and Foggia, as well as in the Molise region in southern Italy. The trend is increasing, as confirmed by the Leone brothers. This is only a small step forward, sadly counterbalanced by a delay in the genetic research and development of our many native varieties, often unsuited for mechanized harvesting systems.

At present, Spanish varieties, Arbequina in particular, are becoming increasingly popular among olive producers. Obviously, preserving the so-called “pricing premium” for made-in-Italy oil will become more and more difficult: all the protagonists of the sector will have to make every effort to define a new communication strategy, free from the stereotypes of tradition, which would be perceived as false.

If we persist with our irrational opposition to every type of scientific research, resting on our laurels, the price that we will pay will only get higher.

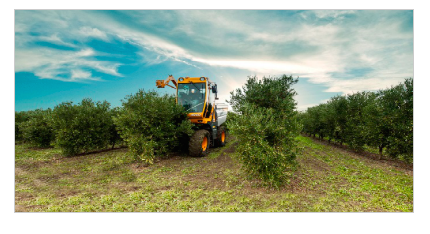

The new farming techniques, and consequently, the opportunity of mechanizing all field operations, can drastically reduce both harvesting costs and times, and ensure the quality of the oil, if processing takes place within a limited number of hours from the harvest.

Consequently, the processing technology must also rapidly evolve to make it more competitive pricewise, so that the quality of the oil reflects that of the olives.

Straddle harvester in a super-intensive olive plantation

Straddle harvester in a super-intensive olive plantation

In the so-called “continuous” harvesting system, the drupes are detached from the tree by means of beaters, which inevitably provoke micro-traumas to the olives. These in theory do not compromise the quality of the oil, but given the large amount of fruits accumulated every hour in the trailers (up to 8 – 10 tonnes), potentially dangerous fermentation processes may occur if the olives are not immediately processed.

Once the harvest is conveyed to the mill, the first thing to do is to separate the olives from the leaves (which can account for up to 10% of the overall weight). In recent years, washers have fallen in disgrace, but it might be worth reconsidering them. These machines exploit a water recirculation system to convey the fruit from the accumulation tanks to the milling system, and clean the olives better than the showers that are now present in most mills. If it weren’t for the technically questionable laws in force, I believe that this would be the best solution.

Mechanically harvested olives

Mechanically harvested olives

Water-recirculating olive washer

Water-recirculating olive washer

Scientific investigations have revealed that olive oil is not merely the product obtained from the extraction of the lipids from the fruits. It is instead a more complex product whose chemical and organoleptic qualities depend on various parameters such as olive variety, sanitary conditions and harvesting time. Other critical factors are those relative to the extraction process, namely its duration, temperature and levels of oxygen.

Malaxation is the most crucial stage in the production of extra virgin olive oil. It can be defined as a bio-enzymatic process, the parameters of which must take into account a variety of elements, such as the cultivar, harvesting time and climatic conditions. Also important is the type of oil one intends to obtain.

Traditionally, malaxation took place at 30 °C for a maximum of 45 minutes. However, recent biochemical investigations and the latest temperature-control technology have revealed that these prescriptions are now obsolete.

Malaxing at a temperature higher that 30 °C raises the amount of polyphenols in the oil, whereas prolonging the process for an hour or more increases the levels of chlorophylls and alcohols, while significantly reducing the amount of esters, and the result is a “ripe fruity” oil.

In their quest for fresher, stronger bouquets, producers have started to harvest much earlier in the season, so it is now time to revise the malaxation process using a scientific approach.

Often, even when the fruits are perfect, the oil obtained does not possess the features the producers hope for. The reason usually lies in the high environmental temperatures (quite normal, in October): the olive paste is often at 30 °C or more, with a subsequent, involuntary, hypermalaxation; the consequences are even worse if the malaxation units are not airtight, because the contact with oxygen, especially at high temperatures, is extremely detrimental.

Recent investigations on the enzymatic processes taking place in the olive paste suggest that it is not always necessary to heat the paste, but rather, it might be best to cool it down to 15-18 °C, so as to limit or inactivate the action of enzymes such as polyphenol oxidases or peroxidases. Only then should the paste be malaxed, possibly in a controlled atmosphere (hence with a limited contact with oxygen), and setting the appropriate times and temperatures for the variety and ripeness of the olives, so as to maximise the phenol content of the oil and protect its most delicate aromatic traits, such as the scent of freshly-mown grass or artichoke.

In order to better control the processing temperatures, adjusting them to the different situations, the malaxing unit should no longer be considered as a heat exchanger, but just a mere churner, to be combined with a modern, high-efficiency heat exchanger.

Alfa Laval plant endowed with a continuous heat exchanger

Alfa Laval plant endowed with a continuous heat exchanger

Research has been given a new lease of live: many new technological solutions are at an advanced stage of experimentation. For instance, we have now concluded the third year of trials using ultrasounds in industrial plants. This technology may be the key to continuous extraction systems, with no interruptions between pressing and centrifugation.

High-frequency sound waves (greater than 16 kHz) both mildly heat the olive paste by mass absorption and cause the physical effect of cavitation, which provokes the rupture of the cell membranes. Sonication can therefore enhance the effects of malaxation, and in some cases, even replace it.

The next couple of years will be fundamental for defining the best malaxation parameters for the type of oil one wishes to produce.

Alfa Laval ultrasound-assisted heat exchanger

Alfa Laval ultrasound-assisted heat exchanger

The article by Domenico Fazio is taken from issue 5 of the Olio Officina Almanacco, a yearly magazine published by Olio Officina and available in all Italian bookstores (click HERE)

To comment you have to register

If you're already registered you can click here to access your account

or click here to create a new account

Comment this news