All the secrets of oil

Interview with Valentina Cardone, Chemiservice. No efficient olive mill can exist unless it relies on a lab that can explore extra virgin olive oil thoroughly, including in sensorial terms. Freshly-produced oils are no longer classified only based on homemade screening of their acidity. Increasingly often, oils are taken to laboratories for analyses that, although fewer than analyses envisaged by law, are sufficient to assign oil to a quite well-defined product category

“Olive mills increasingly tend to rely on external advisors and to cooperate with laboratories, requiring more comprehensive support, besides oil analyses. Some mills now have their own small internal laboratories and have employed technicians it is very interesting to interact with”.

These are the words of Valentina Cardone, Director of the prestigious Monopoli Chemiservice Laboratory, an internationally-renowned facility operating in the Italian region of Apulia, whom we have interviewed to understand how olive oil millers deal with their product nowadays.

Valentina Cardone

Valentina Cardone

The time of improvisation is over, when oil simply needed to be extracted from olives and collected in silos after its free acidity was quickly analysed. Nowadays, olive oil mills working with care and attention, after carefully selecting olives, also need to correctly recognize and identify oil obtained and examine it based on its chemical-physical profile. “Do it yourself” is not the right strategy. What should olive oil mills adopt to be efficient and be confident they are correctly managing oils they produce? Do they need any internal professionals or can they be self-sufficient and rely on external laboratories?

The generation of olive oil millers I have the opportunity to work with and that I personally meet during harvesting time at the laboratory, including cooperatives, local producers and others, is a generation of men (and increasingly often, of women) being surprisingly conscious, skilled and able to critically look at themselves and the others to achieve improvements. The concept of quality, technically speaking, has already entered this universe and it has profitably, in my view. Of course, this is proportionate to producers’ sizes and often to economic resources they have. However, the concept is there and is reflected in several actions that perhaps were not made in the past.

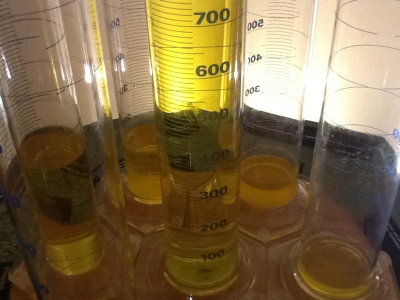

First of all, freshly-produced oils are no longer classified only based on homemade screening of their acidity. Increasingly often, oils are taken to laboratories for analyses that, although fewer than analyses envisaged by law, are sufficient to assign oil to a quite well-defined product category. Olive oil mills increasingly rely on the advice of professionals taking part in all stages of production and making HACCP handbooks useful and necessary. This role is quite often played by olive oil millers who are currently extremely different from ancient stereotypes. Modern mills often have a degree, have attended master courses, specialization courses and regularly pay a visit to their suppliers, carefully maintain their equipment, personally go to the laboratory to deal with issues they are interested in, including land characteristics, irrigation water quality, processing waste disposal, malaxation temperature, packaging issues, storage areas. “Do it yourself” for this kind of olive oil millers is therefore reassuring. It does not jeopardize, but rather give more value to the fruit of their work. However, also those who do not have tools to critically compare and assess their work and products, seemingly tend to increasingly rely on external advisors and on the laboratory, requiring more comprehensive support, which goes beyond oil analyses. Some producers have also built their own laboratory and employed technicians it is extremely interesting for us to interact with.

After initial selection, when it comes to store oil in silos, the hardest part is making blends and bottling. Oil must not only be evaluated in sensorial terms, but, more importantly, traditional analysis envisages compliance with the 28 requirements, each one of which must be checked, so that oils can be classified as extra virgin oils. What is your advice to olive oil mills that want to be sure not to make any mistake?

Olive oils classification stems from requirements and values set forth in Ann. 1 of EEC Reg. No 2568/91, as amended and “amended” means the incredible, gradual, constant effort made by policy makers to introduce new analyses, legal limits variations, decision trees, sample management protocols, control execution and claims management. This regulation indeed includes 21 annexes. Most of them explains the rationale of each analytical requirement and the relevant method. Analyses are envisaged to monitor oil quality and authenticity. There are so many of them. If all are carried out, one can have a thorough overview on the product identity, its characteristics, possible critical issues, strengths and weaknesses. However, analyses to be carried out are normally selected based on practical and limited needs. Essential analyses include acidity, the number of peroxides and spectrophotometric values, in that they assess how fresh the product is. However, in my opinion, one should not neglect monitoring of ethyl esters of fatty acids, because it defines olives health and therefore somehow helps forecasting future oil chemical-physical and organoleptic changes. When all is said and done, these parameters also allow establishing minimum conservation terms for oil. I have noticed that somehow there is reluctance to give samples to laboratories carrying out the panel test, because such test is still considered to be “optional”, as if the relevant parameter, as the aforementioned ones, was not envisaged by policy makers as mandatory to assign the appropriate product category to oil. Although it is sensorial analysis, it does have the same dignity instrumental analyses have and in spite of its critical issues, it is a legal parameter. Obviously, olive oil millers and skilled internal operators’ expertise is crucial to select oils, but it is not formally sufficient to be completely certain about product compliance with prevailing regulations. Oil samples must therefore be entrusted to a professional or official panel certifying compliance. Another important analytical parameter to be noted is determination of stigmastadienes. Their presence in oils indeed reveals contamination of refined olive oils. Though accidental, such contamination leads to non-conformities in extra virgin olive oil. It is not rare that such contamination occurs in production facilities where the same line is used for both packaging of refined extra virgin or pomace olive oils. Or in all cases where working tools (pumps, probes, containers, etc.) that are also used for handling of oils to be refined are not appropriately cleaned. It is crucial to check the efficiency of the self-control system to prevent significant claims in the event of non-conformities emerged during official audits.

In the many years you have dedicated to olive oil, with Chemiservice, you have inherited from your father not only this business, but also a new and original vision, an approach and style in analytical science that has made the difference from laboratories that simply perform analyses, but do not study any new solution. If all jobs evolve in time, what are future scenarios in oil analyses?

Luckily for my sister and I, my father has always had much respect for our cultural interests and inclinations. He has never asked us to study chemistry, agricultural sciences, food technology and to do his job. Following him in his projects and supporting him in the laboratory after my law degree was natural and spontaneous. I have received legal education and my approach in the laboratory does reflect it. I have found out that, in spite of appearance, chemistry and law are not so different: most services offered by the laboratory stem from the need to comply with regulations. In a now quite distant past, food security was an aspiration, something left to the common sense of the industry entrepreneurs. Conversely, today each segment of this matter goes under the lens of policy makers, who issue more or less specific provisions and disclose information using the most powerful media they have. Nowadays, laboratories cannot only perform analyses and summarize their service in numbers. They must be aware of legislation even before operators of the food industry are and, if possible, they must take part in drafting of technical rules and testing of new methods, besides improving existing ones. They must be part of the circles that decide the evolution of analytical techniques and say their opinion, whenever possible. In this way, they can have tools to support customers and help them understanding a service that can no longer be accessible only to those who have specific technical skills. Entrepreneurs coming to our laboratory are seldom chemists or technicians, but they are entitled to fully understand the content of controls they ask us to perform. I perfectly understand this need, as I had to train and understand a language and some concepts that were absolutely stranger and difficult to me. In summary, the future of chemistry applied to olive oils will involve law and science going in tandem. Analytical data will need to be increasingly solid and reliable, understandable to all operators of the supply chain through accessible language and communication.

Olive oil quality has turned into certainty compared to some decades ago. Considering your job and your international vision, in that Chemiservice is a globally-recognized benchmark, when did olive oil millers become conscious of it? What are oils anomalies are identified in?

For some operators, food security and the quality of their products have always been an aspiration and achieving them has been instinctive. For others, they have turned into needs emerged following claims during official audits. For others, globalization and the actual need to export olive oil has made it necessary to gather information on parameters and limits established by internal and external regulations. Also the opportunity to market olive oils in mass retailing has led may producers to adopt systematic quality and authenticity controls.

Based on our experience, the most common anomalies, or rather non-conformities, identified in olive oils are organoleptic defects; values exceeding limits envisaged for spectrophotometry and peroxides (often provoked by inappropriate conservation of oils after packaging and in particular on supermarket shelves); stigmastadienes values exceeding limits envisaged for extra virgin olive oils (often caused by accidental contamination of virgin olive oils with refined/pomace olive oils); higher phytochemicals amounts than established by prevailing regulations for both conventional and organic olive oils; phytochemicals forbidden by importing countries such as the United States.

Valentina Cardone was born in Monopoli, in the Italian region of Apulia, in 1978. After her Law Degree and professional qualification, she studied legal issues related to food production and marketing. Her constant commitment in the Chemiservice laboratory and the strong bond with her father Giorgio led her to deal with olive oils and become a benchmark for producers and packers. Supported by highly-qualified technical staff, she has been the head of Chemiservice project focusing on chemical and microbiological analyses of olive oils and vegetable fats for over thirty years.

To comment you have to register

If you're already registered you can click here to access your account

or click here to create a new account

Comment this news