Corso Italia 7

Rivista internazionale di Letteratura – International Journal of LiteratureDiretta da Daniela Marcheschi

SPLENDOURS, MISERIES, AND POTENTIALITIES OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA (THE BERLIN THESES)1

[di Darko Suvin]

Dedicated to my late comrades from building and thinking Yugoslavia, Marius Broekmeyer, Gajo Petrović, Fred Singleton, and Rudi Supek.

Darko Suvin

0: INTRODUCTORY

THESIS 1: WHY WRITE A BOOK ABOUT S.F.R. YUGOSLAVIA, WHAT IS ITS FOCUS

Contrary to biological and ecological survival of tens of millions, the capitalist denial of all change and adaptation that does not issue in „profit now“ leads to termination of many species, possibly including homo sapiens, certainly including humanity and sapience. To envisage alternatives, among other matters a critical overview of salient aspects of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia or SFRY (as I shall for brevity call the 1945-89 society) is urgently needed.

Only the long-duration, fateful aspects can be focussed upon. The need for SFRY independence, Tito’s great invention, as presupposition to any self-government is taken for granted; I do not deal here with the foreign relations of SFRY, including Tito’s second invention of the “Non-aligned” movement, nor with the pressures on SFRY from the USSR, and later the world capitalist market and its institutions. In my judgment, the crucial factors here were the internal class relationships, which determined how the no doubt strong pressures were handled. Nor do I deal with nationalisms, which become fateful only from the 1970s on, and then because of class necessities. Nor, regretfully, with religion – though I argue that matters of salvation and belief were at the core of SFRY. 2/

The red thread is a use of Marx’s concepts of alienation versus emancipation in permanent shuttle to and from SFRY economics, beliefs, and politics within a critical utopian horizon. His “self-government of the producers” is my concrete utopia.

This entails a strategic limitation of extensive analyses to the period 1945 (or even 1950) to 1972. After that no new factors appear, only the old drawbacks get aggravated.

The analyses are accompanied by hypotheses about the SFRY’s essential tension and about its beginning and end, as sufficient for this attempt.

The essential tension in SFRY is indicated by these citations from Boris Kidrič, the remarkable Politbureau member in charge of the economy, between 1949 and 1952 (see Suvin, “Economico-political Prospects ff Boris Kidrič”):

„T[he basic question] of exploitation of man by man in the system born of the socialist revolution is who disposes of the surplus labour − and behind this questions sooner or later the even more fateful one arises of who in fact appropriates the surplus labour.

State socialism [necessarily grows into] a privileged bureaucracy as a social parasite, the throttling of socialist democracy, and a general degeneration of the whole system, [and there comes about] a restoration of a specific kind, a vulgar State-capitalist monopoly.

The socialist democratic rights of the direct producers [are the obverse of] the process of abolishing monopolies; basic is − the right of the working masses to self-management at all levels of socialist State power.”3/

The same view was later formulated by the loyal Marxist opposition of some intellectuals such as the Praxis group and the economist Branko Horvat.

My stance or Haltung is one of looking backward from the mostly scandalous years 1972-89 and its fully scandalous downfall in the worst imaginable variant of mutually embattled dwarfish classes leading brainwashed mini-nationalisms. This is what has to be explained.

For the context of current events, please see the enclosed CHRONOLOGY OF S.F.R. YUGOSLAVIA.

PART 1: ECONOMICS, CLASSES

THESIS 2: ACCUMULATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS

The precondition for independence, well-being, and modernisation of SFRY was a rapid industrialisation of a semi-colonial country rich in raw materials. The capital for it came from a new “socialist primitive accumulation,” much less cruel than the capitalist one but making for permanent stresses and exploitative pressures. The pressures were tempered by a need for wide plebeian support from below, which ruled out dispossessing peasant smallholders. Capital came later in part from US and international capitalist loans (in 1950-61 around 2.5 billion US$) predicated upon the geopolitical importance of the Yugoslav armed forces in Cold War Europe.

The attendant major social shift in SFRY 1950-72 was the move of between 1.5 and 2 million peasants to the cities. In 1969 the peasantry fell under one half of the total population for the first time since the Neolithic. By the 80s private peasantry seemed to have been less than 1/5 of the population, though many unskilled workers could return to the farm in crises. Another major social shift was the rapid mass production of the first modern proletariat and intelligentsia in this part of the world.

Finally, the source of sufficient capital accumulation was left unresolved. The rise and disposal of the surplus value arising from labour-power, to be balanced between industrialisation, defence, and standard, became a crux. It was the underlying locus of all achievements and discontents.

THESIS 3: CLASSES AND THEIR PYRAMID IN SFRY

Classes are strategic shifters determining how the circulation of goods needed for life interacts with everything else in the human production of life; they are based on unequal appropriation of surplus labour. The strength and reproduction of classes is not exclusively economical but tied to human productivity in the domains of material production, of societal control, and of the symbolic imagination.

After the Partizan victory in 1945, which achieved the eradication of the ruling classes of monarchist Yuigoslavia, all SFRY classes except for peasants were in statu nascendi. By 1971 the class spread had consolidated into (out of a total of 20.5 million people): ruling class, 0.8 million; various middle classes, around 5 million; peasant smallholders, 7.5 million (+ private artisans 0.5 million); manual workers — in industry, transport, building, services — around 7 million (the 1 million workers eventually abroad came partly from working class and partly from peasantry). Since these classes were very unequal in power, control of the conditions of production, material privileges, and collective consciousnesses, this is a class pyramid, albeit of recent formation after much upward mobility and counteracted by officially egalitarian and factually plebeian pressures.

Distinct working class fractions emerged, based on qualification, income, gender, and permanence of employment. Probably there were at least five: the highly skilled workers (9% by 1970) participated more actively in politics and self-management, while on the other end the unskilled ones were more rebellious but less politically conscious and far less organisable. The unskilled and semi-skilled fraction plus a growing number of peasant-workers shuttling between city and country in the 1970s-80s comprised perhaps half of this class, and together with the ca. 30% of women workers probably three quarters. Fractions of the middle classes went from the lowest of technicians and clerical employees to the engineering, scientific, and humanist intelligentsia.

THESIS 4: THE RULING CLASS

In the first 20 years or so Yugoslav classes or class fractions were relatively undefined, even containing contradictory inner tensions. But it seems clear that there were classes of manual workers in agriculture and in industry plus services, a ruling class of collective possessors of economic and political command, as well as intermediate or “middle” classes. The rulers were an oligarchy, evolved out of the symbiosis of the Party top with State power; their core, called by Horvat a politocracy, comprised about 300.000 people, with families perhaps 800.000, and probably acquired in the second half of SFRY trajectory also the junior partner of an evolving managerial “technocracy.”

The existence of a ruling class was officially tabooed or, more rarely, argued against because the Party/State core did not own but only administered the strategic heights of the economy, so that its members could not dispose of it. Yet in Marx’s view property reposes upon appropriation of goods and services by classes in power. While legal status and sanctions are important, they do not determine the central power relationships inherent in all appropriation.

Furthermore, in Marx’s terms of a daily dynamic compulsion for appropriation of labour’s surplus value, there was exploitation of the working class − and other working people − in SFRY. This underlies all the ideological and territorial quarrels within the politocracy about distribution of this surplus. The surplus remained constant at 2:1; that is, two thirds of the surplus labour ended up outside the enterprises and the workers’ disposal.

PART 2: SFRY PARADIGMATICS: THE TWO SINGULARITIES

THESIS 5: POLITICAL CONTRADICTIONS, PRINCIPAL AND SECONDARY

A State ruled by a Leninist party, permanently menaced by world capitalism, has to look to its ideological and material defences. However, the principal contradiction in SFRY after the first few years was one between the budding oligarchy and self-government of the people − that is, who decides how and for what to use the accumulation or surplus value. A small part of the Party tried to think about disempowering the oligarchy. But since the Party’s professional core out of class interest shied away from bottom-up democracy outside, it could not allow it inside either. The SFRY society lived with three major denials, marginalisations or Freudian repressions: of the peasantry, the women, and eventually the not fully employed workers. In the absence of strong working class input into power, a secondary impasse resulted in the form of a veto possibility by the regional oligarchies, which became nationalist and chauvinist as against the federal power top and, aided by foreign factors, led to the demise of SFRY.

The depth events below the historical flow can be illuminated as two groups of major SFRY singularities − within a permanent tension between plebeian democratic power from below versus oligarchic domination from above.

THESIS 6: THE SINGULARITIES’ HYPOTHESIS

The first is a group of creative plebeian singularities. It began as a communist-led popular or plebeian revolution, that created the strong Partizan tradition of do-it-yourself-on the-spot applied in the fighting units, in the network of territorial power (the People’s Councils), and in the political organisations, all participating in an in-depth experience of self-determination. It continued after 1945 as popular enthusiasm for reconstruction of a devastated but now liberated country. It culminated in the secession from Stalin and some top leaders’ rediscovery of their own Partizan roots in Marxian self-rule, which led them to strengthen local centers of power down to the basic territorial units and to slowly introduce self-management in the nationalised enterprises, with centralised but potentially supple planning (the Kidrič model 1951-54). It established a horizon of ethnic fraternity and socialist democracy from below.

This first group of singularities can be read as the Communist Party’s (further as Party) historical block or tacit alliance with the plebeian classes forged at the end of the 1930s and during the Liberation War, refusing fascist imperialism, bourgeois exploitation, and as of 1948 Stalinism. Its strongest bastion was in the self-management system within production and services. By the latter 60s that block was breached, while no possibility of open pressures by the plebeian classes within a socialist democracy was being developed. This is when the Party’s oligarchic core grew into a ruling class.

The second is a group of suicidal class singularities caused by the consolidation of a ruling class that regrouped from the end of the 60s on as, partly, a financial “technocracy” and partly as three major and three or four minor ruling groups in the constituent republics, halting further emancipation of labour and of the public sphere, abolishing efficient planning, and introducing a slide towards nationalism. It held repressively together until the end of the Cold War.

This stagnation or Yugoslav Brezhnevism lost connection to mass energies from below, while the economy grew into a patchwork between a largely uncontrolled profit motive plus consumer market and an inefficiently decentralised “command economy” of the Soviet type. In an unfavourable international political and economic climate these split oligarchic classes finally became as a rule ready to turn into neo-comprador bourgeoisies at the service of foreign financial capital, mainly German.

PART 3: SFRY SYNTAGMATICS: LES VINGT GLORIEUSES [THE 20 GLORIOUS YEARS] AND THE DOWNTURN (1945-72)

THESIS 7: PERIODISATION OF SFRY

From the above flows a periodisation of SFRY history, necessarily disregarding shorter ups and downs and blurred boundaries:

1/ Upward development (ca. 1945-61)

–ca. 1945-52: post-war reconstruction and consolidation, centralist fusion of Party and State, command economy from top down;

–ca. 1952-61: introduction of limited self-management, monolithic unity of Party and State continues, high economic growth;

2/ Plateau stall (ca. 1961-72)

–ca. 1961-65/66: counter-offensive of the conservative majority of politocracy, by the end of this period a ruling class self-conscious of the imperative to keep power against the plebeian classes;

–ca. 1966-72: the lukewarm battle for direct democracy through extension of self-management to the power top has been lost; the ruling monolith fragments into a polyarchy of “republican” power-centres, which mostly welcome the profit principle and slide toward nationalism; beginning of significant economic decline;

3/ Downward slide (ca. 1972 on)

–post-1972: stagnation and ad-hoccery, sharp economic decline. This Brezhnevism could be perhaps divided by Tito’s death, that is: up to 1980, stronger role of politocracy as a confederal polyarchy, after 1980, crisis and weakening in all respects.

This tallies with world history insofar as the definitive break, though prepared in and after 1965, occurs in the early70s. Signalled by the oil crises, it was characterised by the exhaustion of the major impulses arising out of victory against fascism: the militarised Welfare State, the separation of the “Soviet bloc” into a fenced-in subsystem of centralised State planning (leading to Cold War), decolonisation and the Non-Aligned movement. Before that break, revolutionary political pressures allowed economic growth outside the capitalist metropolitan areas, violating exclusive profit logic. It is followed by a period of erosion, crisis, and breakdown of the antifascist phase and eventually the return to “pure” profit capitalism, to all of which Yugoslavia became a prime example.

THESIS 8: THE COMMUNIST PARTY

The Party was the backbone of SFRY ideology, power, and development. In a Leninist revolution, the Party’s role is decisive also after the seizure of power, so that every turning point in mass history is simultaneously a critical internal Party matter. SFRY was a Party-State. Very soon, the Party became a centaur: the head part was a State-Party, the main rump were idealist or careerist followers. Yet there permanently smouldered within it the tension between the horizons of liberation and domination.

Insofar as it was an emancipatory backbone, the Party was a possible feedback instrument for plebeian class interests from below. But since there was no democracy inside it, such pressures were inchoate, leading in practice to an eager or unwilling execution of decisions from the leadership. Insofar as it was an alienated backbone, the Party was a Stalinist „transmission belt“ from the oligarchic core to the population and all institutions. The „cold“ and „warm“ currents clashed within it up to 1971. But in the meantime the Party’s class composition had drastically changed.

In the 50s the Party ceased to be a predominantly peasant one without becoming a working-class one but growing into a party of employees and office-holders. Thus, after the first post-war decade it was a party of people working (or not) by sitting down, rather than of the manual labourers standing up. Finally, it was left without peasants and young people – the latter returned in the careerist 70s – and with relatively few and unimportant women and workers. Thus, it became a party of the ruling class, still allied for a time with some middle classes and supported by a minority of active workers.

The Party’s legitimacy was based initially on the revolutionary achievements of plebeian upward mobility, which changed the life of millions for the better, and the attendant defence of independence. As emancipatory horizons waned, it shifted increasingly to the population’s standard of living. This collapsed in the 80s.

THESIS 9: SELF-MANAGEMENT I: THE PROMISE, THE ACHIEVEMENTS. THE LIMITS

“Self-management” − beginning with Workers’ Councils in industry − was excogitated by the 1949 Communist Party Politbureau as a way out two major problems that could not be solved by centralised State command: first, the need for renewed popular consent and participation in a seriously threatened country; second, the need for rising productivity while preserving social justice. It unleashed major energies and expectations from the working class and the whole “working people” for a thorough redistribution of power downward. When in the 50s independence was preserved and the economy took off, pressure from below gained for the Workers’ Councils a veto on the appointment of enterprise manager and decision power on workers’ income after subtraction of State taxes; also, self-management was extended to State farms, trade, construction, transport, and communications, and later to education, culture, and health services. The battle turned in the 60s to how is the net income to be divided between the enterprise and its Workers’ Council vs. the State. Yet the radical 1949-53 project by Kidrič of “council democracy” from top to bottom, accompanied by flexible planning with input from below, had been abandoned, so that how to decide about investment priorities, prices, subventions, and foreign trade was left to the oligarchy.

The Workers’ Councils were not a full workers’ control, since the appointment of managers was strongly conditioned by the municipality and two thirds of the net income were taken by the State without any worker say. Yet in its heyday of 1958-68 these councils made for a significant worker participation: more in shop-floor and income matters, less in investment decisions. The self-managing collective was composed of manual workers, technicians, professionals, and clerical staff with equal rights of decision, no one could be expelled except for a clear reason and following detailed procedures. The collective had no property rights in the net worth; the results of its activity were sold through the market. All employees of an enterprise were deemed “producers,” including those under 18 and trainees, and elected biennially a non-remunerated Workers’ Council of 15 to 120 members, with three quarters of shop-floor workers, as the supreme management body. The council met monthly, and any member of the enterprise could be present. In 1950-58 membership in Workers’ Councils or its subcommittees involved about one in eight out of over 3 million workers. In the 60s the spread between minimum and maximum income (not counting perks for the top) was between 1:4 and 1:7, and rising. My impression is that up to 1972 the workers’ incomes were decent for those who had their own, very low-rent apartment (but many didn’t), whereas for the skilled workers and the upper half of staff they were good, and for the top staff at times opulent.

Training workers was especially acute in a country where before 1945 there were few industrial, managerial or scientific skills available and two thirds of youngsters still had 4 years’ schooling or less. A large programme of adult education during the first 15 years received generous financing. In its culmination of 1967/68, there were 236 “Workers’ Universities,” which held almost 10.000 courses with 311.000 participants and over 20.000 lectures with 2 million listeners; their number fell abruptly after 1970 in the swerve to a capitalist market.

The Workers’ Council elected a Managing Board of 3 to 11 members as executive organ for current decisions, which in the 70s began to be packed by specialists and to overshadow the parent body. Even before, though power was up to a point shared by the Director and his technical staff with the highly skilled and skilled workers, women and lower ranks only counted in case of general dissatisfaction.

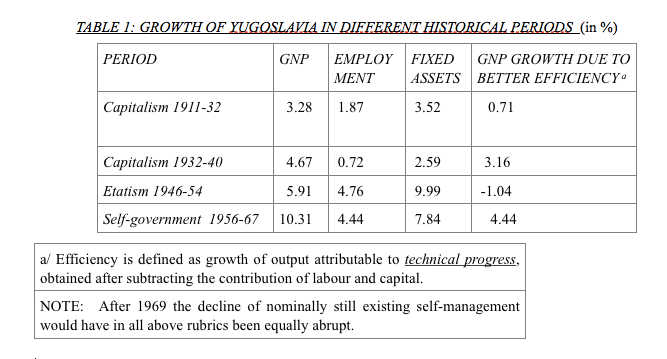

What was the economic performance of Workers’ Councils? In the best informed view of Branko Horvat, up to 1968 very good:

At its height self-management yielded amazing results, absorbing the shocks of urbanisation and of decision decentralisation by creating collective commitment and comradely care. Special praise is due to the vertically organised, truly self-managed and independent, “interest communities” for health, education, science, and culture, which introduced the first wedge of democracy into traditionally patriarchal relations before being neutralised in the 70s. Did self-management economically perform well? In micro-economics odds are that yes, in macro-economics only if and when certain macro-knots were smoothed out — and after 1965, they were not.

THESIS 10: SELF-MANAGEMENT II: THE STALL BETWEEN SELF-GOVERNMENT AND OLIGARCHY

Decentralising without empowering the plebeian classes created a middle layer of powerful State/Party officials in the governments and communes of the constituent republics, anxious to conserve their positions, for whom power was synonymous with opening jobs and extensive economic development. Paid out of taxes on production, this stuck-in-the-mud majority of the oligarchy became the main drag on self-management and democratisation. Therefore, “extensive” and often less than efficient industrialisation was not abandoned.

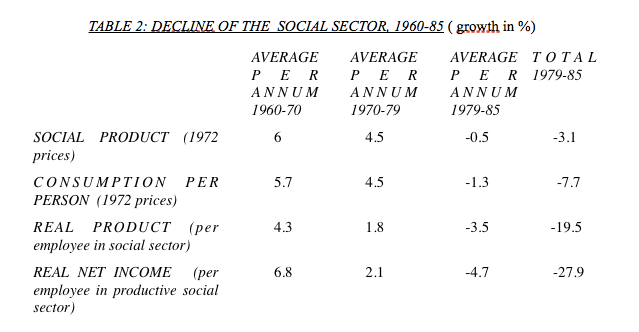

In the 60s the production of raw materials and fuel began substantially lagging behind the production of consumer commodities, many plants operated well below capacity. An attempt at a major reform in and after 1965 failed because, in the absence of a fully developed council system up to the power top, the split inside the Party/State — both at the federal centre and in the assertive republican centres — between equally pernicious conservative etatists and “free marketeers” blocked any clear decision. A compromise was adopted which allowed for much uneconomical decentralisation without specialisation. Despite obfuscating verbiage, the Workers’ Councils were fenced off as a ghetto in “productive” micro-structures only, which reduced them to a caricature. Even so, there was an initial sharp rise in workers’ productivity, largely due to the extension of self-management downward to the enterprises’ “economic units,” while food imports were reduced to roughly the pre-1939 level. However, as the macro-economics percolated downwards, national income growth and efficiency of investments fell drastically, the trade deficit soared to 30% of Gross National Product in 1971 and kept rising. Large disparities in regional living standards, which had diminished in the 50s, rose again. The simultaneous reform of banking created independent capital lenders and burdened enterprises with huge debts, leading to a wave of strikes from end of the 60s on.

This means that the peasants and manual workers were neutralised, impoverished, and atomised. The majority of the middle classes was mired in consumerism, the small radical wing of the humanist intelligentsia was powerless and persecuted. Federal funding was discontinued, except for the armed forces and foreign policy. The ideological and political paralysis after 1965 grew ever more acute in the unfavourable international economic climate of the 70s. The resulting stasis continued for a quarter century:

The main consequences were: conspicuous economic instability and low productivity, leading in the 70s to the second-worst inflation in Europe; alteration of the balance of power between the federal centre and the republics in favour of the latter; and increasing social polarisation reversing the post-war trend, so that a majority of young and unqualified workers could scarcely make ends meet each month.

PART 4: THEORISING LES VINGT MINABLES [THE 20 SHAMEFUL YEARS] AND THE ALTERNATIVE

THESIS 11: ACHIEVEMENTS AND DISAPPOINTMENT

In the first two decades of SFRY the economic and political gains of the plebeian majority were indeed revolutionary: national independence and mass upward social mobility for the plebeian classes, with full employment, free social services (eventually extended to peasants too), and a huge growth of schooling. Up to the middle 60s, the ruling oligarchy mainly formed a historical block with the manual workers and most middle classes in a common effort for a rapid productive and cultural build-up, benefiting a large majority. The hopes and the potentialities accompanying an Industrial Revolution in one generation were great. And the disappointment is correspondingly huge.

THESIS 12: ALTERNATIVE HORIZONS: OLIGARCHIC ECONOMISM VS. RADICAL DEMOCRACY

Due to cultural and economic backwardness and to the absence of a rooted working-class culture, the Yugoslav revolution was necessarily at least as much a “bourgeois-democratic” as a “proletarian” one. It was a peasant revolution led by that combination of dissident intellectuals and internationalist working-class traditions as channelled by Stalinism which was the Communist Party and its youth wing. Any worthwhile mode of living would have to be arrived at by doing after the revolution, almost simultaneously, the work of capitalism insofar as a primitive accumulation to build up industry and tertiary services was quite indispensable, not least to achieve a productive agriculture, as well as the work of communism by creating a new alloy of the ideological, the economic, and the political − a new unity of solidarity.

Self-management had vigorous roots in the Partizan movement that routed the fascist invaders in World War 2. Its tactics rose from the ranks and strongly conditioned the Party’s GHQ strategy; the Partizan system was a self-management system applied to war. However, this alternative was first overlaid by State centralisation in 1945-51 and then, after a decade of see-saw, bit by bit but irrevocably rejected by the late 60s out of fear for the oligarchy’s rule in favour of a „market socialism.“ The market was mystified as a socialist invisible hand and panacea, and ideologically twinned with crass “economism” that denied transparent politics in favour of oligarchic power and quantitative economic investment, jettisoning central planning with mandatory input from lowest levels. The ensuing course led to disaster.

The main lesson is that political and ideological emancipation is indispensable for a full reorganisation of production in a socialist State. Self-management in production and radical democracy are mutually dependent, co-variant.

The interests of the working people are in the long run incompatible with a management of the economy dominated by reproduction of capital, and with the management of societal life dominated by secrecy and monolithism. However, the logic of collective action in favour of socialism in one country was opposed to the logic of capital internationally. Giving in to this second logic, in the last 20 years of SFRY — instead of governmental guardianship over sectoral balance and infrastructural investments for sustained growth and for diminishing class and regional inequality — plans and investments were oriented to the need for foreign earnings and to foreign loans and projects, mainly with IMF financing. The dismantling of the Welfare State began in SFRY before the world capitalist offensive of the 70s, but for analogous class reasons. The final nails in the coffin were the harsh IMF loan conditions in the 80s and the subservience of the degenerated ruling class/es to it.

THESIS 13: SOCIALISM, POLITICS, THE VANGUARD PARTY

I refuse the official USSR and then SFRY notion of „Socialism“ as a separate societal formation, a period on a par with capitalism or feudalism, with connotations of statics and fixity. I cannot dispense with the term, but it is useful only if considered as a field of forces polarised between class society alienation and communist disalienation, connoting dynamics and fierce contradictions on all levels. In this disalienating sense socialism is not simply an economistic alternative to bourgeois society but also, and primarily, a cultural alternative, a different civilisation − the coming about of a different relationship between people as well as of people with nature. Its communism is to be measured according to the degree the society realises Marx’s slogan, “From each according to his capacities, to each according to her needs.” Socialism can never be „built“ as a house, finished once and for all (especially not „in one country“). The purpose of socialism is to shift the balance of forces between class society and communism: it necessarily begins with commodity or capitalist production relationships, regulated by exchange value; when the shift is complete, there is no socialism but only communism, regulated by use value.

Capital and its civilisation means command over labour; communism means that labour commands itself (Marx). Since the struggle is not primarily economistic but ideological and political, socialism is necessarily a political society.

In other words: the aporia of necessary long-duration class, gender, and other negative characteristics within the struggle for a classless society (see Thesis 14, 1-2.) enforces a strategic modification to Marx’s semantics, where politics had the exclusive sense of antagonistic collisions based on class interests. After the 20th Century revolutions, however, we know also of “non-antagonistic contradictions within the people” (Mao). Without civil-society politics to resolve them, only the State remains for that job − a necessary, but very one-sided politics from above. This became the major fault of “actually existing” Leninism, growing out of backward patriarchal realities.

Communism cannot abolish politics, that is oppositions within the civil society between groups with differing interests. Today we may redefine politics as existing outside class antagonisms too, so that its germs could well be present in and intertwine with class politics in the “transitional period.” The State cannot really be abolished until its necessary functions are taken over by associations of producers as well as associ

Per commentare gli articoli è necessario essere registrati

Se sei un utente registrato puoi accedere al tuo account cliccando qui

oppure puoi creare un nuovo account cliccando qui

Commenta la notizia

Devi essere connesso per inviare un commento.